Last time we covered the critical question of maintaining a scaled editing area so that we can work on a 16 bit resolution ILDA file on lower resolution screens. As I mentioned in that post, one of the other areas we want to address sooner rather than later is ‘undo’/’redo’. All modern editors are expected to do this well and users have become accustomed to relying on the feature.

Instead of starting from scratch, our good friend JUCE has an UndoManager class. It is a specialized container class that holds instances of an UndoableAction class. One of the things I like about this setup is you add UndoableAction instances to the manager by “performing” them. That is, the operation is ‘done’ initially by exactly the same code that will be executed for a ‘redo’ operation. This eliminates a common pitfall with undo/redo systems bolted on after the fact, where do and redo are different bodies of code that don’t always stay in perfect sync.

Up to now our FrameEditor worker class has basically had public get and set functions. For example, from FrameEditor.h:

float getRefOpacity() { return refOpacity; }

void setRefOpacity (float opacity);Step one to implement our Undo/Redo system is to make this into three functions, get, undoable set, and destructive set:

float getRefOpacity() { return refOpacity; }

void setRefOpacity (float opacity);

void _setRefOpacity (float opacity);The function _setRefOpacity is just our original setRefOpacity function renamed. This is our “destructive” version of the operation. Our new setRefOpacity function is the undoable version, the one regular clients call. Instead of calling _setRefOpacity directly, it creates an instance of this class and performs it with the UndoManager derived class:

class UndoableSetRefAlpha : public UndoableAction

{

public:

UndoableSetRefAlpha (FrameEditor* editor, float alpha)

: newAlpha (alpha), frameEditor (editor) {;}

bool perform() override

{

oldAlpha = frameEditor->getRefOpacity();

frameEditor->_setRefOpacity (newAlpha);

return true;

}

bool undo() override

{

frameEditor->_setRefOpacity (oldAlpha);

return true;

}

private:

float oldAlpha;

float newAlpha;

FrameEditor* frameEditor;

};

When the class is instantiated it saves the desired new value and a pointer to our FrameEditor worker class. The perform() method saves the old (current) value and sets the new one, using the destructive _setRefOpacity. Undo uses the same function to set the old, preserved value.

One concern with a scheme like this is the scope, or life, of objects. We have an instance of this undoable object class that points to our FrameEditor class. We want to make sure that we never get into a situation where we try to ‘undo’ something after our FrameEditor has already been deleted. I chose to elliminate this possibility by making our FrameEditor and the UndoManager the same object. FrameEditor “inherits” from UndoManager:

class FrameEditor : public ActionBroadcaster,

public UndoManagerIn various object oriented programming paradigms, this is called the “Is-A” vs “Has-A” question. Or, “the entity relationship model”, if you want to sound even more obnoxious. To me it just made sense that our FrameEditor worker class, which we can now ask to perform undoable operations, is the same object we use to undo them.

But, regardless, either having our FrameEditor be an UndoManager or have an UndoManager as a member variable solves our scope problem. The scope, or object life, of our worker class, the UndoManager, and any saved UndoableAction classes that point back to our worker class, are all tied together.

With the Is-A approach, our undoable set function looks something like this:

void FrameEditor::setRefOpacity (float opacity)

{

if (opacity < 0)

opacity = 0;

else if (opacity > 1.0)

opacity = 1.0;

if (opacity != refOpacity)

perform(new UndoableSetRefAlpha (this, opacity), "Background Opacity");

}We make sure the caller isn’t passing in an out-of-range value, check if the request actually changes anything, and, if yes, create and perform the UndoableAction class we defined for this operation (automatically saving it into the UndoManager maintained list).

This works, but we run into one headache. If we grab the opacity slider and play with it, we get a zillion of these events stacked up to undo. Generally, that’s not what the user expects. They have a starting opacity, fiddled with the slider, then stopped. From their point of view, all that fiddling is just one undoable adjustment.

The JUCE UndoManager has a mechanism called “Transactions”, meant to lump multiple UndoableActions into a single undo/redo operation. But it also has a nice rollback feature, which helps us here:

void FrameEditor::setRefOpacity (float opacity)

{

if (opacity < 0)

opacity = 0;

else if (opacity > 1.0)

opacity = 1.0;

if (opacity != refOpacity)

{

if (getCurrentTransactionName() == "Background Opacity")

undoCurrentTransactionOnly();

beginNewTransaction ("Background Opacity");

perform(new UndoableSetRefAlpha (this, opacity));

}

}If we are doing a series of opacity changes, we keep rolling back the transaction to our original value, then adjust to the new one. This turns slider fiddling into a single undo/redo step.

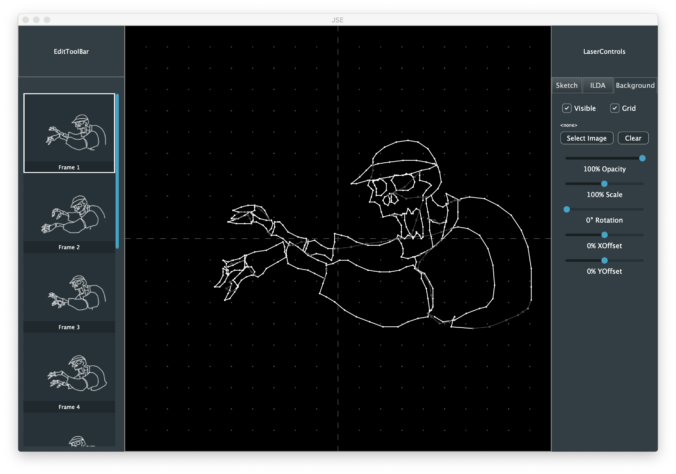

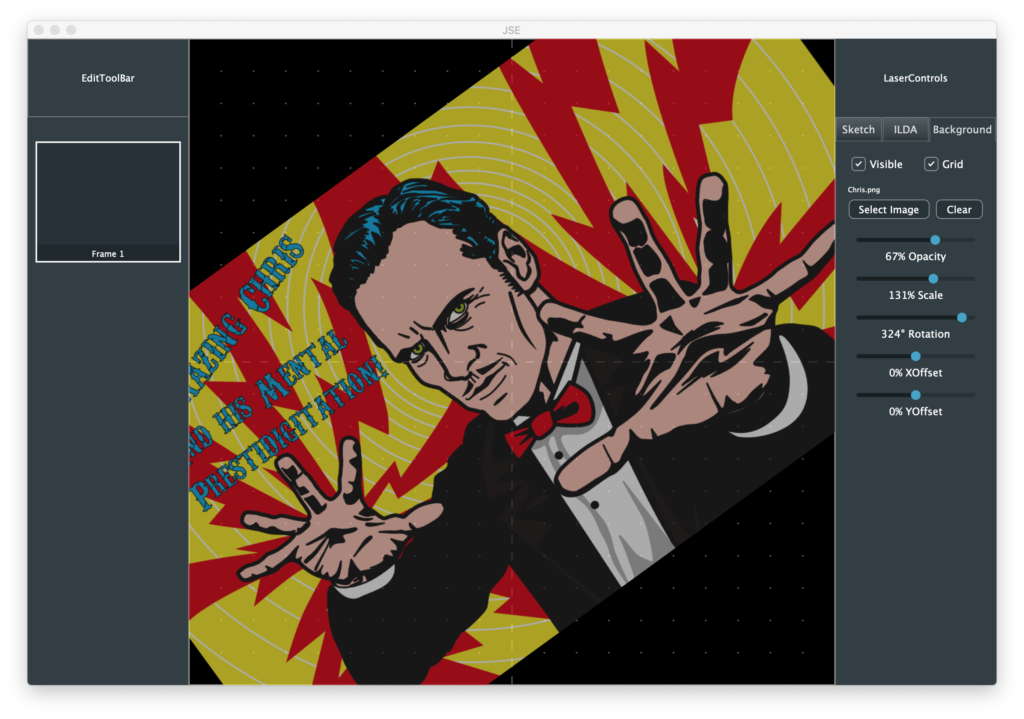

At this point our background layer looks a lot like last time:

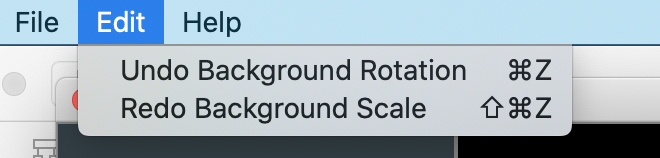

I added a button to clear (delete) the background image and reference grid you can turn on and off, but the big difference is that we can now undo and redo all the adjustments you make:

Now that we have a scheme for undo/redo and a way to scale, draw, and interact with ILDA resolution data, it is time to open some!

The ILDA image exchange format is pretty bare bones. It doesn’t have a mechanism to include vendor specific information. So we will need a to support two formats for opening:

- ILDA (.ild) files

- JSE (.jse) files

A JSE file will contain all the ILDA information, plus all the other items we are tacking on, like our reference (background) and sketch layers. For the time being I’ve decided not to embed any selected background images, thumbnails, etc. in our JSE file. Background images will be kept as a media reference (file name/location), and thumbnails will be reconstructed at load time.

Without raster graphics content, storing coordinates, sketch objects, etc. as ASCII text seems fine to me. JUCE has great support for reading and creating XML files, so we’ll start there. This should make our files easy to examine and fiddle with by eye in a normal text editor. If file sizes becomes an issue we could use JUCE’s wrappers for zlib to compress our XML files in the GNU zip format.

But first things first, let’s just parse an ILDA file and put it into one or more Frame objects for us to manipulate with our FrameEditor helper class!

The ILDA load function in IldaLoader.cpp looks a lot like our ILDA code in our scan system firmware:

bool IldaLoader::load (ReferenceCountedArray<Frame>& frameArray, File& file)

{

FileInputStream input (file);

if (input.failedToOpen())

return false;

frameArray.clear();

// Loop until we are out of frames

do

{

Frame::Ptr frame = new Frame;

ILDA_HEADER header;

// Read the header

if (input.read (&header, sizeof(header)) != sizeof(header)) break;

// Valid?

if (header.ilda[0] != 'I' || header.ilda[1] != 'L'

|| header.ilda[2] != 'D' || header.ilda[3] != 'A') break;

uint16 rCount;

rCount = header.numRecords.b[0];

rCount <<= 8;

rCount += header.numRecords.b[1];

// 0 records marks end

if (!rCount) break;

int n;

for (n = 0; n < rCount; ++n)

{

Frame::XYPoint newPoint;

// We have 5 different handlers for the 5 different

// ILDA data formats (ugh)

if (header.format == 0)

{

ILDA_FORMAT_0 in;

// Try to read the next point

if (input.read (&in, sizeof(in)) != sizeof(in)) break;

// Change endian and store X, Y and Z

newPoint.x.b[1] = in.x.b[0];

newPoint.x.b[0] = in.x.b[1];

newPoint.y.b[1] = in.y.b[0];

newPoint.y.b[0] = in.y.b[1];

newPoint.z.b[1] = in.z.b[0];

newPoint.z.b[0] = in.z.b[1];

// Store status (minus last frame indicator!)

newPoint.status = (in.status & 0x7F);

// Lookup and store colors

newPoint.red = IldaColors[in.colorIdx].red;

newPoint.green = IldaColors[in.colorIdx].green;

newPoint.blue = IldaColors[in.colorIdx].blue;

}

else if (header.format == 1)

{

ILDA_FORMAT_1 in1;

// Try to read the next point

if (input.read (&in1, sizeof(in1)) != sizeof(in1)) break;

// Change endian and store X, Y and Z

newPoint.x.b[1] = in1.x.b[0];

newPoint.x.b[0] = in1.x.b[1];

newPoint.y.b[1] = in1.y.b[0];

newPoint.y.b[0] = in1.y.b[1];

newPoint.z.w = 0;

// Store status (minus last frame indicator!)

newPoint.status = (in1.status & 0x7F);

// Lookup and store colors

newPoint.red = IldaColors[in1.colorIdx].red;

newPoint.green = IldaColors[in1.colorIdx].green;

newPoint.blue = IldaColors[in1.colorIdx].blue;

}

else if (header.format == 2)

{

// Color Palette

ILDA_FORMAT_2 in2;

// Try to read the next point

if (input.read (&in2, sizeof(in2)) != sizeof(in2)) break;

}

else if (header.format == 4)

{

ILDA_FORMAT_4 in4;

// Try to read the next point

if (input.read (&in4, sizeof(in4)) != sizeof(in4)) break;

// Change endian and store X, Y and Z

newPoint.x.b[1] = in4.x.b[0];

newPoint.x.b[0] = in4.x.b[1];

newPoint.y.b[1] = in4.y.b[0];

newPoint.y.b[0] = in4.y.b[1];

newPoint.z.b[1] = in4.z.b[0];

newPoint.z.b[0] = in4.z.b[1];

// Store status (minus last frame indicator!)

newPoint.status = (in4.status & 0x7F);

// Store colors

newPoint.red = in4.red;

newPoint.green = in4.green;

newPoint.blue = in4.blue;

}

else if (header.format == 5)

{

ILDA_FORMAT_5 in5;

// Try to read the next point

if (input.read (&in5, sizeof(in5)) != sizeof(in5)) break;

// Change endian and store X, Y and Z

newPoint.x.b[1] = in5.x.b[0];

newPoint.x.b[0] = in5.x.b[1];

newPoint.y.b[1] = in5.y.b[0];

newPoint.y.b[0] = in5.y.b[1];

newPoint.z.w = 0;

// Store status (minus last frame indicator!)

newPoint.status = (in5.status & 0x7F);

// Store colors

newPoint.red = in5.red;

newPoint.green = in5.green;

newPoint.blue = in5.blue;

}

else

break;

// Store the point

frame->addPoint (newPoint);

}

if (n != rCount) break;

// Don't store palettes!

if (header.format != 2)

{

frame->buildThumbNail();

frameArray.add (frame);

}

}

while (1);

if (frameArray.size())

return true;

return false;

}

All read coordinates are converted into 16 bit X, Y, and Z data with truecolor (8 bits R, G, and B) data. If you look at frame.h, the Frame::XYPoint data type is just the ILDA_FORMAT_4 under a different name:

typedef ILDA_FORMAT_4 XYPoint;

typedef enum {

BlankedPoint = 0x40,

LastPoint = 0x80

} Status;If you skim the code above, a few things might stand out. First, we ignore custom palettes. If a file uses indexed colors, you get the ILDA standard palette. If this turns out to be a real problem, it wouldn’t be hard to fix. I am just reluctant to code something that I don’t even have a suitable sample file to test with!

Another thing that might catch your eye is that we discard the “LastPoint” status bit. We don’t need it in the editor, we keep all the coordinates for a Frame in a juce::Array container class:

Array<XYPoint> framePoints;This way, we can copy, paste, and reorder at will without worrying about keeping the flag in the right spot. We just have to be sure to add it back in when we export our point array to an ILDA file!

The code above also might look like it leaks memory. We allocate a new Frame class with “new” at the top of every iteration of our do loop:

// Loop until we are out of frames

do

{

Frame::Ptr frame = new Frame;

But we never delete it and only conditionally add it to the frame array that the caller passed in. This is a variation on RAII techniques we discussed before with std::unique_ptr and juce::ScopedPointer.

Those classes delete what they point to when they go out of scope, which isn’t what we want here. Just as FrameEditor “Is-A” UndoManager above, every instance of the Frame class now “Is-A” ReferenceCountedObject:

class Frame : public ReferenceCountedObject

These are pretty much what the name implies. The class has a counter. When the counter is decremented to zero, the object is deleted. When our object is created, we put it in a special kind of Pointer class called “Frame::Ptr”. This is just shorthand for the long winded:

ReferenceCountedObjectPtr<Frame>;

This incremented our count from 0 to 1. IF we add it to the frame array, which you can see is a long winded reference counting version too:

ReferenceCountedArray<Frame>& frameArrayThe count is incremented from 1 to 2. The next time we assign a new pointer at the top of the do loop, the previous object is decremented (2 to 1 if saved, 1 to 0 and deleted if not). Similarly, when our function ends, any object in the pointer is decremented and conditionally deleted when the pointer class itself is destroyed.

We didn’t have to use reference counted objects just for our ILDA loader. The std::unique_ptr class has a release() method specifically to transfer ownership of a pointer to another container. But reference counted Frame objects are also useful for undo/redo. Instead of making fresh copies of every frame we delete, etc., we can just hand off the pointer to the UndoableAction class variant and release our reference count on it. Whenever the UndoManager releases the UndoableAction class, the reference will be again decremented and, unless it is still referenced by other instances of undo operations, deleted.

In addition to an ILDA file loader, I added a helper to build thumbnail images, which the loader indirectly invokes for each frame saved:

// Don't store palettes!

if (header.format != 2)

{

frame->buildThumbNail();

frameArray.add (frame);

}

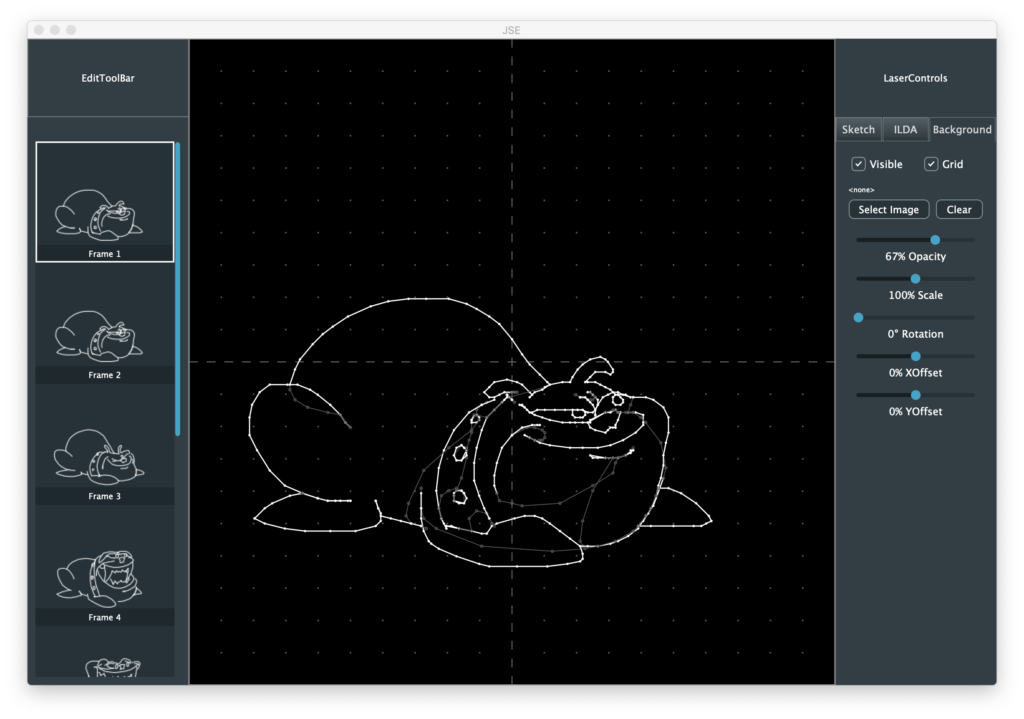

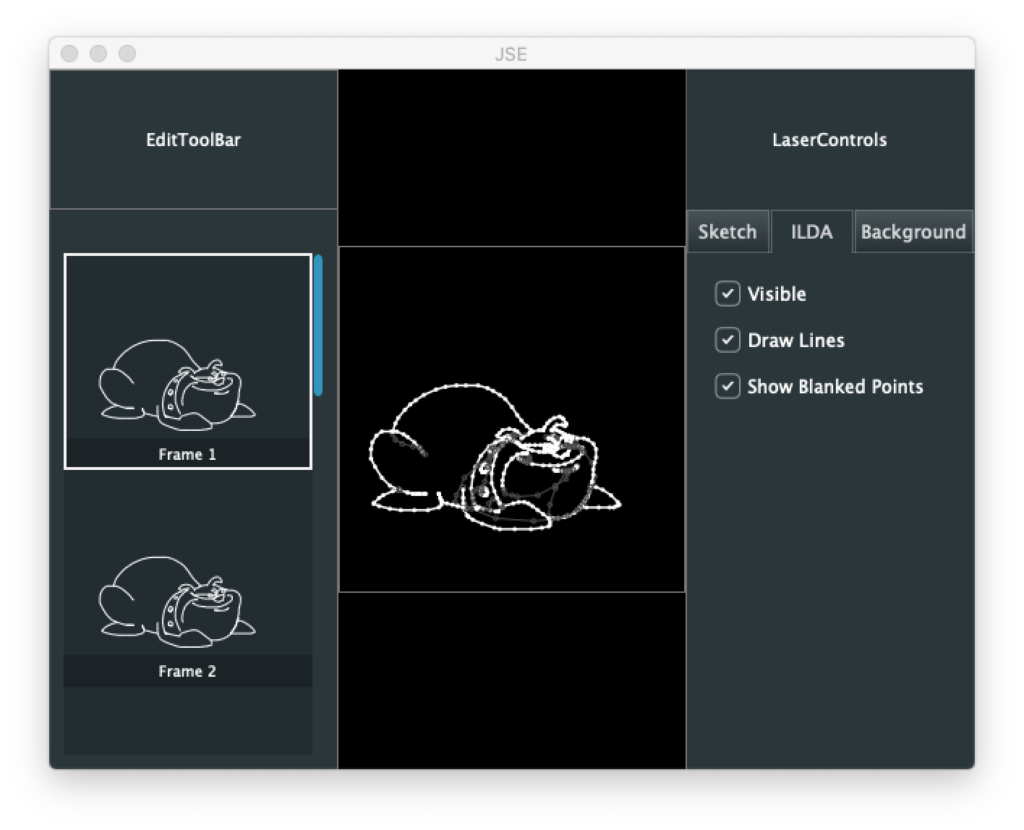

I then modified the FrameList component so that it “Is-A” ListBoxModel, for a ListBox added to it. We are going to have to make our own specialized version of ListBox later when we add advanced Frame operations, but this at least gives us a way to preview and select Frames now:

I actually made the generated thumbnails have transparent backgrounds and made the frame labels a semi transparent bar over the main working area. I wanted the thumbnails to be useful without being too visually distracting. Particularly when an image is in color:

And, believe it or not, this Barney animation is even worse when you project it. But it’s better than anything I have ever drawn, is colorized, and Hanna Barbara likely won’t sue me, so… here it is.

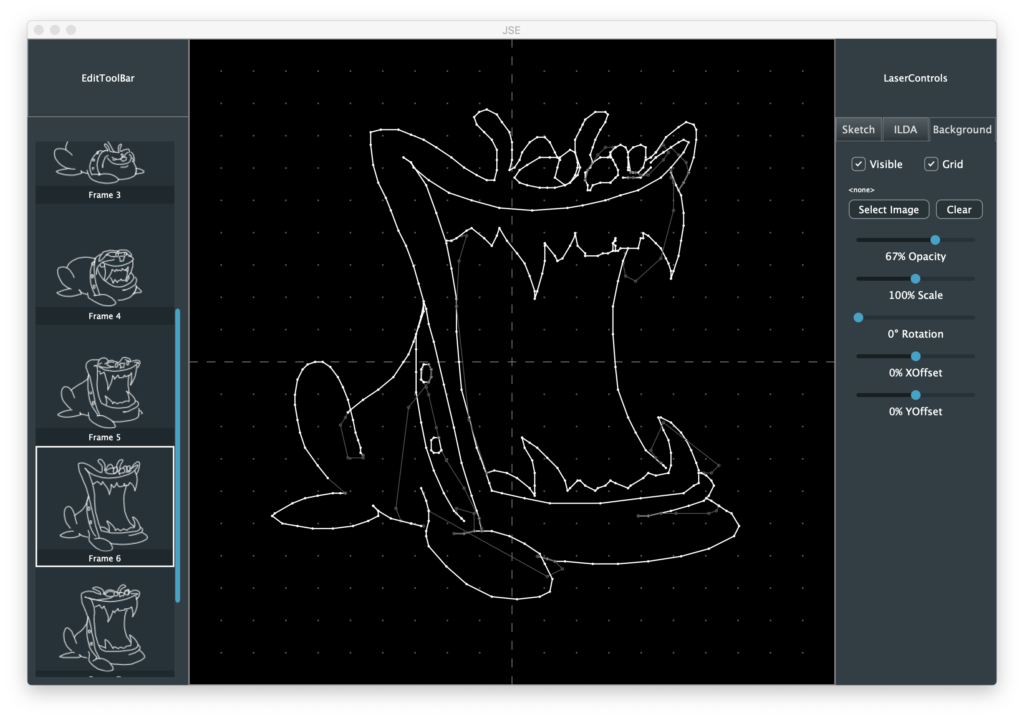

Anyway, I also added some controls for ILDA layer display. Here is with the reference layer grid turned off:

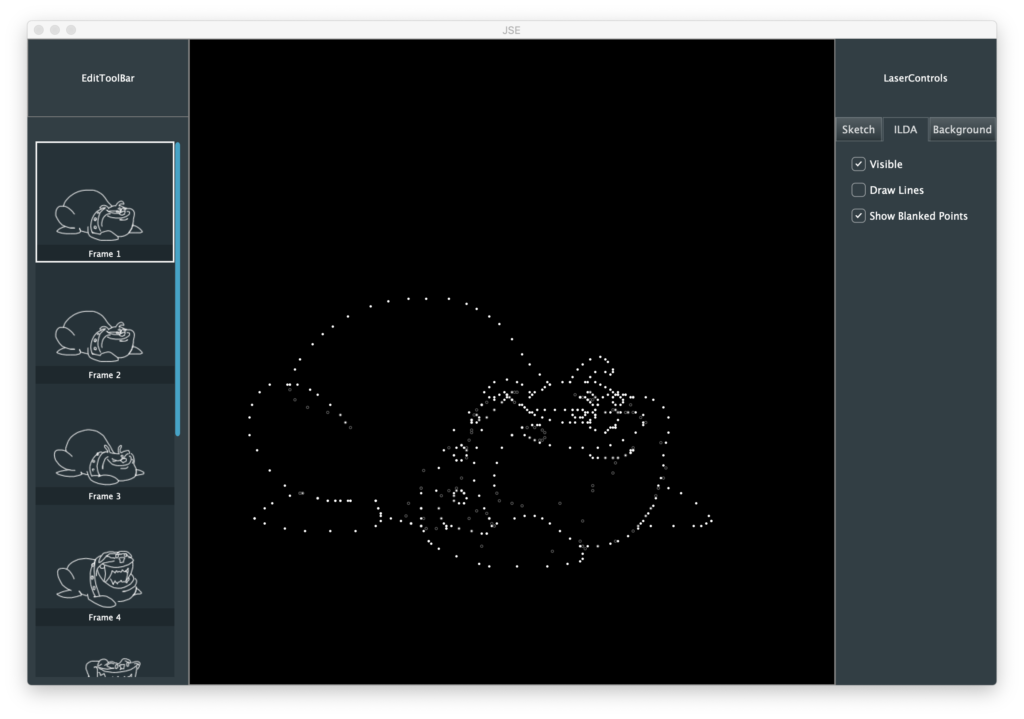

You can turn off the blanked points:

Or hide the point to point connecting lines:

It’s worth reiterated that this is being drawn in our WorkingArea component at full ILDA resolution. The only math we do for coordinates is the arithmetic to shift from center 0,0 to top left 0,0:

// Draw the dots

if (point.status & Frame::BlankedPoint)

{

if (frameEditor->getIldaShowBlanked())

{

g.setColour (Colours::darkgrey);

g.drawEllipse((float)(point.x.w + (32768 - halfDotSize)),

(float)((32768 - halfDotSize) - point.y.w), dotSize, dotSize, activeInvScale);

}

}

else

{

g.setColour (Colour (point.red, point.green, point.blue));

g.fillEllipse(point.x.w + (32768 - halfDotSize), (32768 - halfDotSize) - point.y.w, dotSize, dotSize);

}

This is great for maintaining registration of everything we draw, etc. but what about our circle, dot, and line sizes? We want those to relate back to something that makes sense to the user on the screen, not ILDA resolution. For now I scale them to a target number of pixels on the display:

float dotSize = 3.0f * activeInvScale;

float halfDotSize = dotSize / 2.0f;

This makes things look at little thick when we make the window really small:

And a little thin when we maximize on a big monitor:

But it is a good starting point. We can add a 2nd order proportional adjustment later. After we spend some time editing content. Speaking of which, next stop, let’s start selecting and editing ILDA content and get our Sketch layer going!